Sacred Vessels, Part 3: Chalice

Part 2: Pyx

Part 1: Ciborium

Ok, so it's been waaay too long since I have posted in this series. I apologize. But here is part three, on perhaps the most readily recognized of the sacred vessels. In fact, the chalice is not merely the most easily recognized and named vessel, it has often been used, both visually and literarily, to stand for the Eucharistic sacrament in its entirety, and especially the Precious Blood.

The chalice is also the oldest sacred vessel - Christ did not use a ciborium at the Last Supper, but he did indeed use a chalice, the Holy Grail. Not only is the chalice the original sacred vessel, but it has possessed an amazing continuity of form -- the historical variation in design is not significantly greater than that between chalices found in the various churches of a given city. Like just about everything else in the world, the rules covering chalices were simplified by reforms following Vatican II. Also, the use and definition were stretched by the inclusion of the Precious Blood in the communion of the faithful, and the necessitated use of many simpler vessels for this purpose.

The earliest Christians, due to the persecuted nature of the faith and the pecuniary uncertainties of their stations, relied for the most part on far simpler vessels for the mass than would become customary (and in fact obligatory) later. Records indicate that glass was widely used for chalices, and that precious and base metals, wood, ivory, and even clay were also in use. However, St. Augustine's account of gold and silver chalices excavated (ie, which were already very old in the 4th century) near Cirta, as well as the writings of St. John Chrysostom

indicate an early development of preference for the use of precious metals when possible.

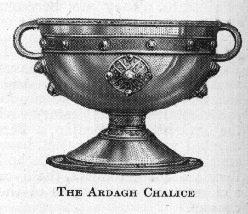

More modern chalices tend to have stems (like the one seen above), but earlier chalices seemingly were more bowl-like, with handes and a base connected to the cup by a knop. The chalices used in older times for the communion of the faithful were larger, and more likely to be fitted with handles than those used solely by the priest. The handles, of course, provided more security against drops and spills, given that it was, as the Catholic Encyclopedia says, "a more barberous age." As an extra safeguard against such accidents, the use of a straw or reed for the people to receive through was widely adopted. Apparently the practice is (was?) preserved in the solemn papal high mass, in which the chalice is taken to the pope on his throne and he receives through a golden pipe. Having never been to any papal mass, I can't say whether this practice actually survives to the present day or not, seeing as there is no longer such a thing has a "solemn papal high mass." The practice is still permitted, however (see here, #103).

During the Middle Ages a series of councils promulgated formal restrictions on the production and use of chalices, forbidding wood. Also banned since then (and this answered a question I had after reading Instruction Redemptionis Sacramentum) is horn, since it is formed with blood. Brass and copper were prohibited because they rust, but pewter was allowed for the poor because it does not. The same document that restricted deteriorating metals proscribed the use of glass vessels for the first time. Throughout the later medieval and into the renaissance period, chalices grew taller, slimmer, and acquired a more elongated stem. The decline in the distribution of the Precious Blood seems to have gone hand in hand with this development, as the sleeker and less stable cups were more fit for use by the priest alone.

Chalices for many years were permitted to be made only of gold, silver, or (when rendered necessary by poverty) pewter. The inside of the cup was to be gilt in the last two cases. Rules promulgated after Vatican II allow more latitude in material, but the requirement for gilding the inside of a non-golden vessel remains. Glass and earthenware are still explicitly prohibited, although hardwoods are not, provided they are "prized in the region" and possess "artistic merit. " Flagons, bowls, and other irregularly shaped vessels are prohibited. Note that the prohibition against glass and irregular containers does not apply to the cruet or bottle in which the unconsecrated wine is brought forth during the presentation of the gifts, as it never contains the consecrated Precious Blood. (That is, the unconsecrated wine should all be poured into chalices and the previous container removed prior to the consecration -- "fracturing," or pouring of the Precious Blood from one container to another, is not permitted). A chalice must be consecrated (and not merely blessed) by a bishop using sacred chrism. The regilding of the cup used to require the vessel's reconsecration, but this is no longer the case. A broken or damaged chalice, however, loses its consecration.

The Precious Blood is ordinarily not reserved -- the norms require that the priest consume all remaining after communion. However, it can be reserved for very specific purposes and for very short periods of time (like the medicine dropper viaticum example Fr. Fox discussed). This is a change from ancient custom, when the sacred blood apparently was reserved in large quantities within specially consecrated amphorae. St. Ambrose mentions this practice.

File Under: Sacred_Vessels

3 Comments:

This is a great article! Paul, I strongly recommend you write an encyclopedia article on this over at the Catholic encyclopedia.

Just follow this link and click on edit at the top and type away. Again, I learned a lot in this article.

http://en.wikikto.org/index.php/Chalice

(You'll need to copy that into your browser)

Here is an article on the history of the chalice as well:

http://www.sanctamissa.org/en/sacristy/sacristy-sanctuary-and-altar/chalice-and-paten.html>

PS: And here is the text of the traditional consecration of a chalice and a paten.

http://acatholiclife.blogspot.com/2009/08/consecration-of-paten-and-chalice-in.html

Post a Comment

<< Home